Blake Little : préserver l'humain, pour changer

L'artiste américain Blake Little a "préservé" des êtres humains dans le miel, une matière magique qui rappelle l'ambre, et peut dans de bonnes conditions se consommer des milliers d'années après avoir été récolté.

L'artiste américain Blake Little a "préservé" des êtres humains dans le miel, une matière magique qui rappelle l'ambre, et peut dans de bonnes conditions se consommer des milliers d'années après avoir été récolté. Pour vous dire la vérité, les photographies et l'expérience nous ont intéressé, mais de là à en dire beaucoup plus... nous étions un peu à sec. Et puis nous avons trouvé ce texte de Kenneth Lapatin, Associate Curator of Antiquities au J. Paul Getty Museum, que nous aurions été bien incapables d'écrire, faute de connaissances sur l'archéologie, et, autant l'avouer, beaucoup d'autres choses. Notre démarche, dans ces cas-là, ce sera de vous proposer des documents, à l'occasion très complets et très sérieux, "universitaires" comme on dit, pas forcément avec le respect qui devrait leur être dû. Une des choses dont Nuit & Jour est protégé, avec sa politique d'abonnement pour les articles, c'est de devoir absolument tout vulgariser et résumer. Profitons-en vraiment.

"Preservation has many meanings, from the physical to the spiritual. At the most basic – and perhaps the most important – level it can denote survival. Hence the idea of protection, inherent in the term. But while the word often implies a kind of stability, or even stasis, preservation also comes about through transformation: wild animal preserves come to exist only by being separated from hunting grounds; fruit preserves are made from hours and hours of boiling, creating a sweet, lasting essence.

There are many means to preservation, some deliberate, others haphazard. Archaeologists usually encounter the latter, for what has survived from the distant past almost inevitably comes to us through chance: thrown into a trash heap, lost at sea, or buried by volcanic ash – only to be rediscovered by accident.

Since its invention in the 1800s, photography has been employed as a key tool of archaeology, capturing images of not only finds, but also the very processes of recovery. Its capacity to record the details of perishable objects – to preserve them – is evident in historical photographs of now degraded artifacts and of excavation sites , many substantially transformed by the very act of digging them and scarcely recognizable today. But today we are also well aware that photography can be far from objective; that it can be manipulated; that it can create something entirely new, original, and surprising.

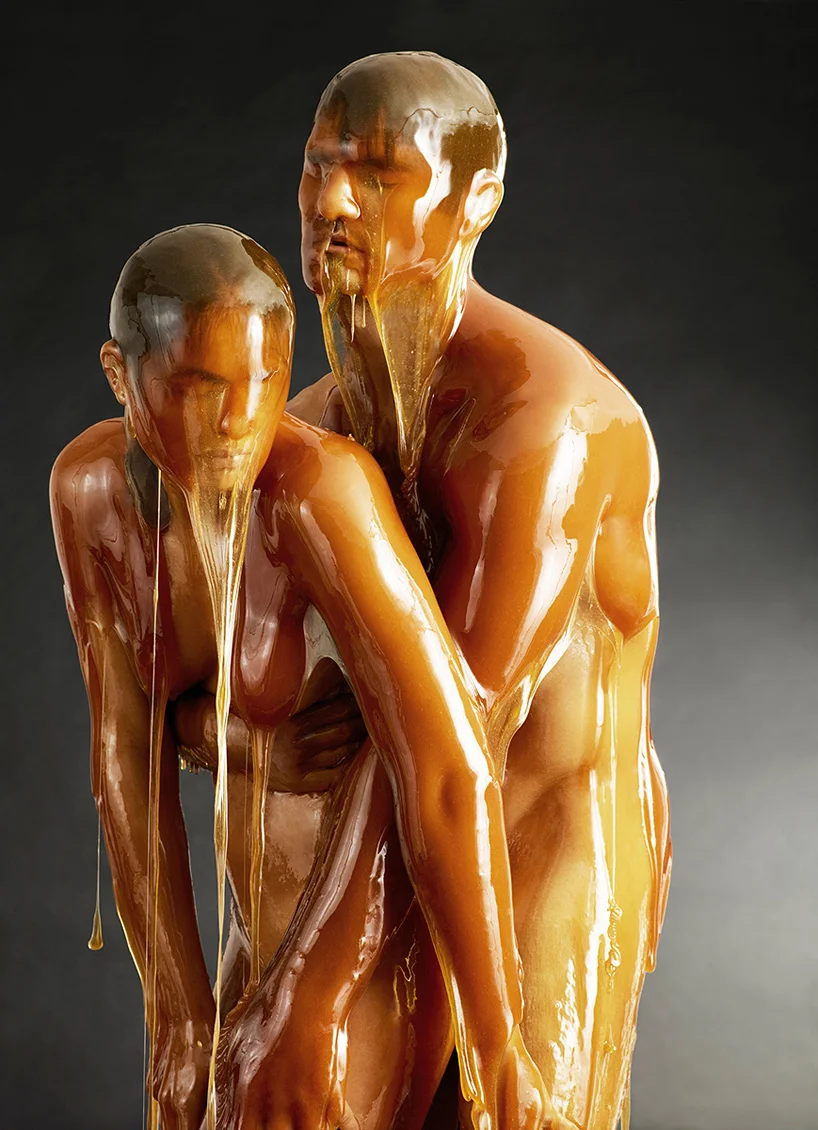

Blake Little’s series of photographs presented here combine the old and the new in a bold way. His vivid images startle the viewer. They freeze the human form, preserving it not in proverbial amber, but rather – and unexpectedly – in honey, another natural substance millions of years old. (For honey bees date back some 25-50 million years, preserved in the fossil record of the Eocene–Oligocene boundary.) Just when and where humans first braved the sharp sting of bees to steal their honey we do not know. Cave paintings in Spain depict human honey-gatherers, and from the time of the Egyptian pyramids, about 2575–2150 BC, what scientists now call the “honey-bearing” bee (Apis mellifera) appears to have been domesticated.

As there was no cane sugar in the Old World, honey was highly valued for its sweetness, but for other qualities as well. It can function as a medicine as well as a preservative, for under the right conditions does not spoil. Honey sealed in ancient tombs can remain safe to eat to this day. In Egypt and other early cultures around the world it was offered to the gods both in its semi-liquid state and in the form of honey-cakes. Greek and Roman poets wrote of pouring libations of honey mixed with milk or wine, and it plays a significant role in several ancient myths. It was honey’s viscosity, as well as its color, transparency, and luminosity that compelled Blake to experiment with the material. Innovatively, he applied the substance to the human body, first in drips, then in sheets, creating gleaming, vibrant forms, which, though far from imitative, recall, in different ways those made by Auguste Rodin, Francis Bacon, and Jeff Koons.

Blake saw – and was intrigued by – the juxtaposition of the timeless, pure substance and human flesh, so prone to decay. He was amazed by honey’s transformations when dripped, dribbled, and poured over the human body, and how it can distort and amplify forms, highlight physical perfection, engender repulsion, and suggest both immortality and death. For Blake, gleaming, golden honey has a way of diffusing the personal qualities of his subjects, often making them unrecognizable, democratizing their individual traits into something altogether different and universal. Sometimes terrifying, it can seem to encase his subjects, almost larvae-like in a primordial ooze, as in Ouriel, front, 2012. At other times it is dynamic, its lively motion captured and frozen, in a very different sense, through stop-action imaging, its tendrils – almost electric – spinning forth (Clayton, 2013). Powerfully muscular bodies, like Devion, back 2012, and gracefully balanced poses, such as Tala, standing up, 2013, evoke works of classical art, such as the famous Discus-thrower of the ancient Greek sculptor Myron. Other images recall sober portraits of the Renaissance (Dylan, 2012; Brad, 2012 and Zayden, 2013), or the dainty ballerinas of Degas in Lindsay, 2013.

Whether thick or thin, the substantiality of the honey is ever present, and because the experience of being covered in it is far from natural – indeed, can be suffocating – many of the subjects seem to struggle, while others surrender themselves to it. In this, and in other ways, the images in these pages recall those (made familiar by photographers of a very different era) of the plaster casts of the victims of Vesuvius, whose bodies have disappeared, but whose evocative forms remained in hollows in the ash that buried them during the disaster that destroyed the ancient cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum during the eruption of A.D. 79, which, paradoxically, simultaneously destroyed and preserved them and have become something of a byword for the fleetingness and unpredictability of human life.

Howsoever intense, grueling, and frightening it may be to be covered by cascading sheets of honey, all of Blake’s subjects fortunately remain very much alive – thanks both to the marvelous properties of this age-old material and the evocative power of his evolving art."

Kenneth Lapatin

Associate Curator of Antiquities, J. Paul Getty Museum